by Sarah Kliff on April 9, 2014

Saskatchewan is a vast prairie province in the middle of Canada. It’s home to hockey great Gordie Howe and the world’s first curling museum. But Canadians know it for another reason: it’s the birthplace of the country’s single-payer health-care system.

In 1947, Saskatchewan began doing something very different from the rest of the country: it decided to pay the hospital bills for all residents. The system was popular and effective — and other provinces quickly took notice. Neighboring Alberta started a hospital insurance plan in 1950, and by 1961 all ten Canadian provinces provided hospital care. In 1966, Canada passed a national law that grew hospital insurance to a more comprehensive insurance plan like the one that exists today.

Saskatchewan showed that a single-payer health-care system can start small and scale big. And across the border, six decades later, Vermont wants to pull off something similar. The state is three years deep in the process of building a government-owned and -operated health insurance plan that, if it gets off the ground, will cover Vermont’s 620,000 residents — and maybe, eventually, all 300 million Americans.

"If Vermont gets single-payer health care right, which I believe we will, other states will follow," Vermont Gov. Peter Shumlin predicted in a recent interview. "If we screw it up, it will set back this effort for a long time. So I know we have a tremendous amount of responsibility, not only to Vermonters."

When Shumlin ran on a single-payer platform in 2010, it was unprecedented. No statewide candidate — not in Vermont, not anywhere — had campaigned on the issue, and with good political reason. Government-run health insurance is divisive. When the country began debating health reform in 2009, polls showed single-payer to be the least popular option.

Shumlin just barely sold Vermont voters on the plan (he beat his Republican opponent by less than one percentage point). Then, he got the Vermont legislature on board, too. On May 26, 2011, Shumlin signed Act 48, a law passed by the Vermont House and Senate that committed the state to building the country’s first single-payer system.

Now comes the big challenge: paying for it. Act 48 required Vermont to create a single-payer system by 2017. But the state hasn’t drafted a bill that spells out how to raise the approximately $2 billion a year Vermont needs to run the system. The state collects only $2.7 billion in tax revenue each year, so an additional $2 billion is a vexingly large sum to scrape together.

Shumlin knows what he’s up against. "I don’t underestimate the challenge," he said. "I know how hard this is, getting to the finish line. There are a thousand swords that could stab us in the heart. My question to the folks who wish for that to happen is, what’s your idea?"

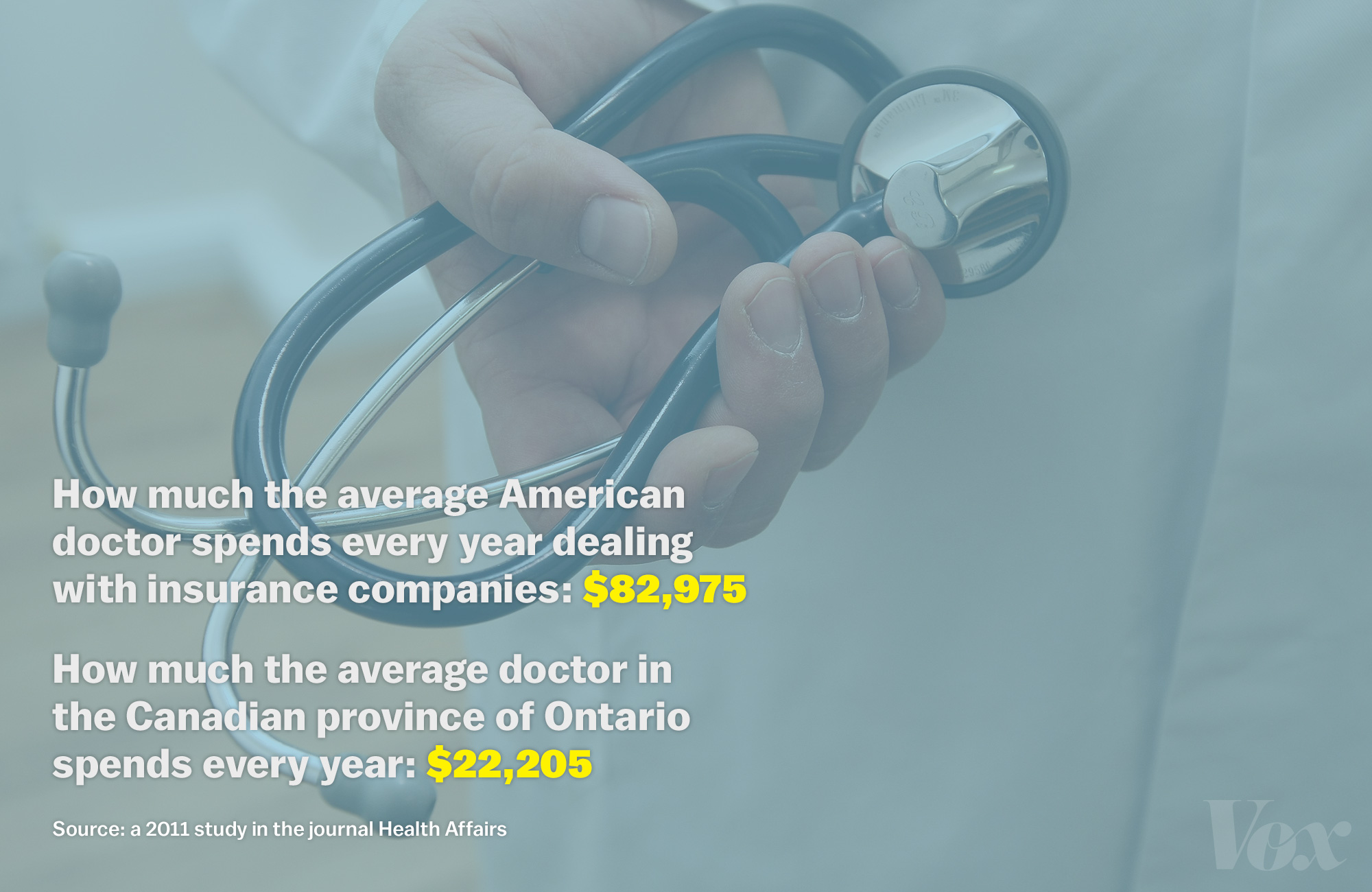

Vermont’s case for single-payer health care can be summarized in one number: $82,975.

That’s the amount a 2011 study in the journal Health Affairs found the average American doctor spends on dealing with insurance companies. Across the border in Ontario, doctors spend about a quarter of that amount — $22,205 per physician — interacting with the province’s single-payer agency.

American doctors spend lots of money dealing with insurers because there are thousands of them, each negotiating their own rate with every hospital and doctor. An appendectomy, for example, can cost anywhere from $1,529 to $186,955, depending on how good of a deal an insurer can get from a hospital.

The amount of money spent on health care averaged out per person has more than doubled since 1999 in Vermont, from $3,421 per person each year to $7,876 per person each year. The gap between the US’s per-person spending and Vermont’s per-person spending has decreased. Source: The Green Mountain Care Board

That doesn’t happen in single-payer systems. When the government owns and operates one health insurance plan for all residents, it sets a single price for each medical procedure. It’s that simplicity that tends to be single-payer’s biggest selling point, and the reason at least a dozen countries around the world use that type of system.

Single-payer systems can vary dramatically from country to country. "It’s a label that gets applied as if you could put a bunch of countries under it, and they would all look similar," says Cathy Schoen, a senior vice president at the Commonwealth Fund, a nonprofit that focuses on health policy research. "But there actually aren’t very many health-care systems that look the same."

Some countries, like Canada, own the health insurance plan but contract with private hospitals and doctors. They pay claims in the same way American health insurers do. Others, like the United Kingdom, own the health-care providers themselves.

Countries make different decisions about which medical services they’ll cover — and how much they’ll ask citizens to chip in. New Zealand and Norway’s programs include co-payments for trips to the hospital; Italy and Denmark do not. Some plans include prescription drug coverage, while others stick residents with the tab.

Overall, single-payer systems tend to be especially good at two things: increasing health coverage rates and holding down health care prices. Getting people covered is, unsurprisingly, a much easier task when the government is running a health insurance plan. When Taiwan implemented a single-payer system in 1995, the insured rate went from 53 to 96 percent in nine months.

Single-payer systems also tend to have lower prices because the government is negotiating one rate for all citizens. Think of it as a bulk discount: when the government can promise to deliver loads of patients to a given hospital or doctor, they have lots of leverage to insist on a lower price. Administrative costs tend to be lower, too. Instead of dealing with dozens of insurers who set hundreds of prices, doctors only need to send bills to the federal government.

The administrative savings of a single-payer system do come at a price. Single payer requires the government to make difficult decisions about what benefits they will and won’t cover — and often leave out pretty standard medical services, things like prescription drugs or dentist visits. Vermont, for example, is still working through whether its plan will include dental coverage, a service that would add at least $218 million to the system’s annual price tag.

The United Kingdom has had especially high-profile fights over what its National Health Service will pay for. The National Institute on Health and Care Excellence (known, funnily enough, as NICE) decides which benefits the national system covers, sometimes setting criteria based on a resident’s age or health status. Women over 40, for example, are only eligible for one cycle of infertility treatment, while younger women get three — a guideline based on research finding younger women have greater odds of conception. NICE has dozens of guidelines, all meant to steer a limited set of health funds to the most effective treatments.

Single-payer countries are often associated with longer wait times, a perception that stems from Canada’s system. One recent Commonwealth Fund survey found 36 percent of Canadians say they wait six days or more to see a doctor when they’re sick, compared to 23 percent of Americans. Long wait times don’t appear to be systemic to single-payer systems, though. Australia and the United Kingdom, for example, have shorter wait times than the United States.

Worries about rationing and wait times make single payer a polarizing term, even in deep-blue Vermont. It’s often used in attacks on government-financed health care, conjuring up images of long wait times and rationed care. Supporters of single-payer don’t like to use it, instead preferring to discuss universal coverage or publicly financed health care. Shumlin is among the rare few who will use the term liberally, mostly out of convenience. He hasn’t found a better term that describes what he wants to bring to Vermont: a system where a single entity (the state) pays for everyone’s health care. And he doesn’t care to spend much time thinking up a better description.

"I don’t care what you call it," he says. "I care that we get it right."

Vermont prides itself on passing bills first. It was the first state to abolish slavery in 1777 and, in more recent history, pioneered same-sex civil unions with a 2000 law. It’s a tiny state that’s fiercely independent: Montpelier’s 7,000 residents like to boast that they are the smallest state capital, and the only one without a McDonald’s.

Vermont wasn’t satisfied with the health reform law that Washington passed in 2010, the Affordable Care Act. That law expands health coverage by growing the existing health-care system. Americans who already had health insurance have seen barely any change. Uninsured people have gotten covered through two existing programs: the individual insurance market (where millions of Americans now receive subsidies to help buy coverage) and Medicaid, a public program for low-income people.

Shumlin had a different idea. He didn’t want to build on what existed. He wanted to blow up what exists and replace it with one state-owned and operated plan that would cover all of Vermont’s residents — an example he hopes other states could follow.

So in 2009, when he was serving as President Pro Tempore of the Vermont Senate, he got in touch with William Hsiao, an internationally renowned expert who has worked with 10 countries building such systems. Shumlin invited him to Montpelier to discuss his experiences. Hsiao — who helped Taiwan build its single-payer system to cover 23 million people — politely declined.

"I was very busy, and I said, ‘I can’t really take the time to drive up to Vermont and talk you through this,’" Hsiao says of his first conversation with Shumlin. "But I told him I would set up a phone conversation."

One phone call led to others, and finally a visit to Montpelier, where Hsiao testified before the legislature about his experiences — and became convinced that, if single-payer health care had shot in the United States, it would be in Vermont.

"My opinion about single payer in the United States is that there are so many powerful political groups, like the American Hospital Association and the American Medical Association that dominate Washington, that it can’t really happen," Hsiao says. "In Vermont, there’s much more grassroots activism."

Shumlin surprised local activists by running for governor in 2010 on a single-payer platform. While most Democrats across the country shied away from health care in that election, reassuring angry constituents that they didn’t support a government takeover of health insurance, Shumlin was on TV expressly endorsing that idea.

"It was the first person I ever heard in politics who was a serious candidate, said the words ‘single payer,’ and weren’t using them in an attack ad," recalls Deb Richter, president of Vermont for Single Payer. "It was amazing."

Shumlin wanted to move quickly. He continued to work with Hsiao, who wrote an outline for Vermont on what their plan could look like (the document is ubiquitous in the state house, known simply as the Hsiao report). On May 26, 2011, Vermont passed Act 48, the first law in the nation that provides health coverage to all residents of a state. Act 48 established Green Mountain Care, a health insurance plan that all Vermont residents would gain access to, by virtue of being Vermonters.

Green Mountain Care cannot start until 2017 because the Affordable Care Act requires states to hew to the federal health reform model for the next three years. This is frustrating for Vermont’s single-payer supporters, who want to put the new system in place sooner.

"When I ran for governor, I had it in my mind…I could find a way to get around it," Shumlin. "My team finally convinced me — and it took some convincing — that it couldn’t be done without losing all our federal funding, which would be suicide. So my goal is to get this done as close to January 1, 2017 as we possibly can."

Between now and then there are two big questions that Vermont has to answer: how much will single-payer cost, and can the state find a way to pay for it?

Putting a price tag on Vermont’s single-payer plan has been a maddening task for health economists. The state hasn’t yet decided which benefits it will cover or how much it will ask Vermont residents to chip in. Then there are other, difficult-to-predict factors like how much, exactly, single-payer will reduce administrative costs or drive down prices.

But getting this right is crucial. There’s a political imperative not to ask for too much money from the state’s citizens, especially when the new system is supposed to save money. But ask for too little and the system might not have enough to cover all their medical bills.

"There are so many different factors and you could end up with a gazillion options," says Katharine London, a health economist at the University of Massachusetts. "When you make choices on some of these things, they all have repercussions in terms of cost."

The Shumlin administration contracted with London and a team of economists last year to estimate the cost of Vermont’s plan. Their report estimates that Vermont will need to raise an additional $1.6 billion in tax revenue in 2017 to pay for a single-payer system.

The Shumlin administration is quick to point out this isn’t the same as increasing healthcare costs by $1.6 billion. When there’s a single-payer system, lots of people who currently pay private insurance premiums won’t. Instead, Shumlin and his team expect the system to cut $36 million in statewide health spending in its first year, largely by reducing administrative spending.

Total estimated statewide health care costs, 2017-2019 (in Millions). Source: State of Vermont Health Care Financing Plan

Vermont’s doctors and hospitals are skeptical of this estimate — and generally protest the idea that the single-payer system will lead to administrative savings. They contracted with Avalere Health, a DC-based research firm, to publish a report that estimates the single-payer system will require $2.2 billion in new revenue to start.

Hospitals don’t think that Vermont’s single-payer system will significantly reduce administrative costs. Right now, they see lots of patients from neighboring states, people who won’t be part of the state-run plan. And that means they’ll still need to deal with multiple payers, and all the different prices they set. Fletcher Allen, Vermont’s largest hospital, estimates that about a quarter of patients are not Vermonters.

"In Vermont we’ll go from four to five commercial payers to one," Fletcher Allen chief executive John Brumsted says, "But we still have a dozen or so more than we’re negotiating with and interacting with in Northern New York and New Hampshire. We still have to have the infrastructure in place to support multiple payers."

In the Vermont legislature, most people ballpark the cost of single-payer somewhere around $2 billion — and spend even more time worrying about how to raise that money. Single-payer opponents have already begun framing it as the largest tax-increase in Vermont history, which worries those trying to shepherd it through the legislature.

"You are raising $2 billion, and that’s just such a significant amount of money," Shap Smith, the speaker of the Vermont House, says. "Even if it’s not new money and just a different way of raising it, that’s still a tough transition. There’s so many people who have a stake in the way things are currently done, and getting them to see that a different way would be better is difficult."

Vermont isn’t alone in its money problems. Single-payer countries around the world have regularly struggled with figuring out the best way to pay for the system. Countries take different approaches to funding single-payer systems. Some pull the funds from a general revenue stream while others create a specific premium tax that goes towards health care. Hsiao had suggested the premium tax approach for Vermont, but the legislature didn’t include a financing plan in the 2011 legislation.

"We recommend that Vermont have a payroll tax contribution designated for health specifically," he says. "Canada doesn’t have such a system, so during a political recession they may decide to cut health care to support education. We designed a system for Vermont where you can’t get into that situation and protect revenue for health care."

Whatever way Vermont ultimately pays for the single-payer system, it will be a noticeable tax increase for Vermonters. There are only four taxes in Vermont right now that bring in more than $100 million annually — the largest of which, the payroll tax, nets $624 million.

"If you look at the landscape of taxation here, there’s no one place to go to raise the money," says Steve Kappel, a Vermont consultant who worked on the Hsiao report. "You’d have to raise the sales tax by something like 146 percent, which is not going to happen."

About half of countries who attempt to build single-payer systems fail. That’s Hsiao’s estimate after working with about 10 governments in the past two decades. Whether he’s in Taiwan, Cyprus, or Vermont, the process is roughly the same: meet with legislators, draw up a plan, write legislation. Only half of those bills actually become law. The part where it collapses is, inevitably, when the country has to pay for it.

"Sadly to say, half of them were never able to pass legislation or once they passed legislation, like Cyprus, the president changes and the new president never really implements the plan," Hsiao says.

Vermont is now in that middle ground. Legislators are worried that they might be losing momentum and are clamoring for the governor to releasing a financing plan.

The state needs to secure a waiver from the federal government for their single-payer plan. Vermont leaders worry that, if they wait too long, they may no longer have a sympathetic president in the White House. And even writing the waiver request means that Vermont has to explain to the Obama administration how they’ll pay for universal coverage.

"We’re running up to the end of an administration that is sympathetic to the reasonable chance of one that is unsympathetic," Peter Galbraith, a member of the Vermont Senate’s finance committee, argued at a hearing in late March. "If this doesn’t go into effect in 2017 it will never happen."

The Shumlin administration had initially said it would release a financing plan this spring, but has since pushed the deadline back to the end of the year. The governor says he’d rather have a plan that’s right than one that’s rushed. "We haven’t figured this one out yet," Shumlin says. "Every time you think you have the answer, there are ten people who will point out the flaw with that particular answer. And they’re usually right."

When Shumlin thinks about Canada’s system as it is today, there are certain parts of it that he likes — mainly that it covers everybody. "Canada has many virtues of their health-care system, mostly that it’s universal," he says.

But right now, he sees Canada more as a cautionary tale than an inspiration. The government has found it increasingly difficult to pay for its health-care system, which has grown from 7 percent of the economy in 1975 to 11.4 percent in 2011. Over the same time period, Canada’s system has grown to rely slightly more on private funding, asking citizens to pay a bit more of their overall costs.

"The problem is they haven’t gotten costs under control," Shumlin says. "They’ve got a publicly financed system that is on steroids sucking up dollars because it relies on the same failed fee-for-service model as American health care. I believe we’re going to have to come up with our own way of doing this in America."

Editor: Eleanor Barkhorn

Designers: Georgia Cowley, Warren Schultheis

Developer: Yuri Victor

Special thanks: Josh Laincz